It’s been a hot minute, but I have a notes app list of ideas to write blog posts about! So I’m hoping to get back into the swing of things.

It always seems to be this time of year I get the urge to post on my blog. I think it’s because Beltane is the summation and epitome of everything my ‘path’ celebrates: sexuality, vitality, Celtic storytelling, sacred union, love, the faery world, the Sovereignty Goddess. Beltane is the festival in which we celebrate the marriage between the archetypal Celtic Queen and King. Of course, this marriage is the metaphysical basis for all the seasons, and the sovereignty goddess is the central axis upon which the festivals spin around, but if I had to choose one Celtic holiday to sum up the ‘Celtic Hieros Gamos’ it would be Beltane. I have made a number of posts referencing these ideas now, which you can find if you scroll back through my blog.

The Faery Queen and her Human Consort

As a Priestess of Rhiannon in training, one of the main Sovereignty stories I’m thinking about this particular Beltane is the story of Rhiannon and Pwyll from the first branch of the Mabinogi. Most of you reading this will already be familiar with the story, but if not, I recommend reading or watching a summary of it first. This story will feature heavily in the latter part of the post.

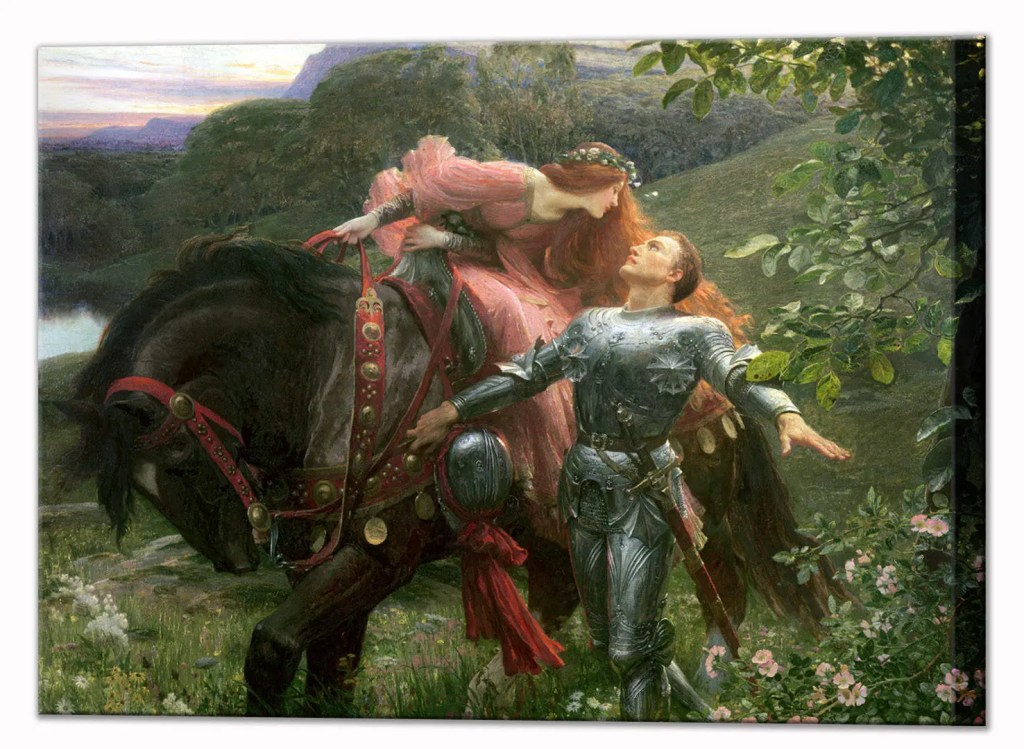

Rhiannon’s story is only one story in our collective Celtic consciousness about the ‘Faery Lover’ or ‘Faery Bride’- a mystical woman, arguably a goddess, who comes out of the mists or the waters or some other liminal faery gateway to take a human man as her lover. Quite the far cry from the timid medieval princess being married off to a stranger for the benefit of her father’s worldly kingdom, the Faery Lover often has agency, and chooses her lover for herself. In many of the stories, she only chooses a man who is already in right-relationship with the land and the world of Faery, and through her divine sexuality that anoints and empowers, he becomes a king. There are different versions of the Faery Lover/Queen/Bride motif, however- sometimes, the Faery Bride does not have much say in the matter, but usually when she is married off against her will, or is mistreated by her human husband, tragedy befalls the man or his kingdom. The Faery Queen/the Sovereignty Goddess will not accept marriage or sexual union with a man she doesn’t choose without putting up a fight. Sometimes, she is the hinge in a love triangle between two men who represent the polarities of Winter/Summer, Old/Young or the Otherworld/This World, and betrays one for the other to represent the changing of the seasons or the ruling order of the realm. Sometimes, she presents her human lover with trials or challenges, which represent the man’s initiation into kingly, divine masculinity. We see this in stories of Courtly Love, where the Lady, such as Guinevere, represents the Faery Lover/Queen. We also see this with Morgan le Fay, who is usually presented as an adversary to Arthur’s knights rather than a lover to most of them, but nevertheless falls into the archetype of the Faery Queen ‘cruelly’ presenting the knight (male initiate) with trials, which ultimately make him into a better, stronger man.

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl

The ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ trope, is a phrase that describes a pattern in (mostly modern) storytelling. In MPDG stories, we begin with a normal, average Joe, ‘everyman’ type of guy, often with a mundane office job that takes up the majority of his time. He goes home to his apartment every evening, watches the news, eats dinner, and goes to sleep, and then repeats this every day hereafter apart from on the weekends where he does some equally mundane ‘normie’ leisure activity. His life is fine, he may be slightly depressed, but he’s otherwise ‘just getting on with it’. Until one day, he meets this woman. She is larger-than-life, quirky, interesting, bohemian, devil-may-care, eccentric, mischievous, philosophical, ‘different’. She enlivens his world in a way he hasn’t experienced since he was a child. Sounds romantic, right? Except often, the MPDG has no goals or desires of her own. She exists to ‘enlighten’ the male protagonist, to be projected upon in his quest to bring whimsy and magic back into his life, and that’s it. Some writers play with deconstructions of the trope, in which the MPDG may actually be mentally ill (‘manic’ in a literal sense) and thus deeply troubled (Effy from Skins, Alaska from Looking For Alaska), or they show that the male protagonist was only using her in his quest for self-discovery and abandons her when he has absorbed enough of her sparkle. He may also try to make her ‘normal’ by the end of the story once he no longer needs her to be her faery-esque self, both in critical deconstructions of the trope or uncritically in media utilising the trope itself (typically older media). We see this archetypal pattern play out in real life, too. Tropes are just media versions of archetypes, and archetypes define our lived reality.

If you ask me, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl can be seen in two ways that are interconnected: 1) A modern version of the ‘Faery Lover’ archetype, and 2) Man’s subconscious desire for sacred union with the Divine Feminine, or Goddess. The MPDG shows him there is another way to live, another way to view the world. His world is black and white before he finds Her, who fills it with vibrant colour. She is his initiator into the ways of the Divine Feminine.

Human Women Aren’t Goddesses

Now, I don’t actually think this is inherently a bad thing at all. I actually think it’s beautiful that women can help men enter sacred union with the Goddess. Women represent the portal between this world and the Otherworld, through our wombs that can be seen as portals. This is why I think stories of a free, lively woman brightening up a man’s life can be a representation of something both real and healthy: the way feminine power can be a true blessing to men. The problem lies wherein the man forgets that his woman is not actually the Goddess, but a human woman. Yes, she has the Goddess within her, and he recognises that. She becomes a mirror to him, and in seeing Goddess within her, he finds God within himself. He realises there is more to this world than his 9-4 office job, the pub and watching the evening news. But she is not actually the Goddess, and both parties must remember that. I truly dislike the new age spirituality trend of human women being called ‘goddesses’. I find it both blasphemous hubris, but also dangerous to a woman’s spiritual journey, especially if she is having this projected on to her by a male partner who expects her to be the perfect image of the infallible, shining Venus, with no ‘human baggage’. And in the oldest stories, Venus isn’t always the radiant, exalted Queen of Heaven. She also finds herself on her hands and knees, in the Underworld, stripped of all her power. Men raised in a patriarchal society (which is most of them) often have a much easier time accepting the light feminine than the dark. The woman’s partner who is projecting his desire for the Goddess onto her may not accept this cthonic aspect of her inner Venus, especially if he has not integrated his own shadow. The idea that projecting an image of Venus/the Goddess onto human women can be contrary to women’s liberation is also present in criticisms of Courtly Love, wherein the idealised Lady was seen as functionally identical to Venus or the Virgin Mary. Whilst Courtly Love certainly did uplift the status of women in my opinion, it is valid to claim it is not identical to the aims of today’s feminism. Feminism needs to allow room for women to make mistakes, to be human. In order not to fall into this idealisation/pedestal pitfall, it may be helpful for a man to meet and integrate his own inner feminine first before becoming the lover of an archetypal ‘Faery Woman’, or to already have a relationship with the Goddess without the need for a female partner to be a perfect reflection of Her for him. Just like how it is helpful for women to learn to ‘rescue themselves’ without needing their Prince Charming to do it for them. This doesn’t mean a woman cannot love the structure and safety provided by the Divine Masculinity in her male partner, or that a man cannot love the magic and radiance provided by the Divine Femininity in his female partner, but that in order to avoid falling into projecting an unrealistic ideal onto your partner, you must find it in yourself, or in the actual Divine, first.

Another problem that might occur when a ‘Normie’ Man falls for a Faery Woman that her way of living and viewing the world may not always serve him and his lifestyle. What happens if he wants her to prioritise a corporate job and make more money, but she would rather work fewer hours in order to honour her feminine cycles and need for rest? What happens if he wants her to be more ‘normal’ before his friends and family, but she refuses to hide her true self? What happens if their parenting styles clash because she wants to homeschool their children in a wild and holistic way and he’d rather them go to a traditional school? The man may unconsciously believe that the ‘Otherworldly Faery Goddess’ nature of his partner may be nice in the bedroom, or when he needs a break from the slog of his 9-5, but not in the ‘real world’. The very qualities he once loved about her now become something he comes to dislike. The man may let modern society’s patriarchal norms colour his perceptions of his ‘Faery Goddess’, and he may come to see her ‘Faery Goddesss’ traits as ridiculous, uncivilised or unhinged, where he once saw those same traits as the missing puzzle piece in his life. He tries to ‘tame’ her.

Rhiannon and Pwyll

In the first branch of the Mabinogi, before Pwyll even meets the otherworldly faery goddess/queen Rhiannon, he goes on an initiation through the Otherworld as a favor to Arawn, the king of Annwn (sometimes seen as interchangeable with Gwyn ap Nudd). Rhiannon, presumably hearing of this brave and adventurous man in her own faery world, comes to earth to seek him out to be her husband, despite being betrothed to another man. By being already initiated in the ways of Faery, Pwyll impresses Rhiannon, and the two end up marrying. But despite his Otherworld initiation, they do not live Happily Ever After. When Rhiannon is struggling to conceive a child, Pwyll’s court and people began to turn on her. Finally, she gives birth to a beautiful, healthy baby boy and is in their good graces again. But when their baby disappears from Rhiannon’s bedside in the middle of the night, Rhiannon’s cowardly handmaidens, fearing they’ll be blamed, smear their sleeping mistress with puppy blood, and accuse Rhiannon of killing her own son. Rhiannon doesn’t fight back, and takes the blame, in what I personally perceive to be an act of compassion and grace for her handmaidens not unlike Jesus dying on the cross for the sins of the world, as well as perhaps resignation that she wouldn’t be believed even if she defended herself and denied wrongdoing. While it doesn’t say this in the text, I imagine Pwyll’s court and people would’ve had an easy time accepting Rhiannon’s guilt because they likely already viewed her as ‘other’. She came out of the worlds of Faery. She is different, potentially dangerous, to these human tribes who have already at this point began shifting into true patriarchy, which views the feminine and the Faery realms as something to fear. Sound familiar? Like I said earlier, a man can turn on his MPDG or Faery Lover once other people’s thoughts and opinions get into his head. Rhiannon’s Otherworldly nature, that Pwyll once adored about her, is now something to be feared- Nature and powerful women something to be feared, as was quickly becoming a core axiom of the new patriarchal order that was falling out of harmony with the subtle, mystical, and arguably feminine Otherworld.

In punishment for the crime of infanticide she did not commit, Rhiannon is sentenced to play the role of her mare for years, offering to carry visitors to Pwyll’s palace on her back. The mare, once a symbol of her power and sovereignty, has now become a symbol of her shame and humiliation, just like her Faery nature has now become something to be feared and reviled.

Later on, finally, Rhiannon is vindicated. A peasant couple found her baby in their stable, and have been raising him for years. He is strong, healthy and unharmed. The kingdom rejoices, and so does Pwyll, but he never so much as offers her an apology in the story. Rhiannon names her son Pryderi, meaning ‘anxiety’, to represent the years she spent mourning for him and fearing that he is dead.

After Pwyll presumably dies, Pryderi arranges a marriage between his mother and Manawydan fab Llyr, who is often interpreted as the god of the sea. You can take this as a patriarchal act of a woman needing to have a husband to be provided for, and her son handing her over to her new ‘master’, but you can also take it, as I tend to do, as it being Rhiannon’s choice. As I mentioned earlier, many ‘Faerie Bride’ stories feature a love triangle between her and two men representing the polarities of Dark/Light, Old/Young or Mystical Otherworld/Ordered Civilisation. While Pwyll had made his Otherworld journey and at one point was in alignment with the Otherworld, he arguably fell out of alignment with it when he humiliated Rhiannon in favour of the anxieties of the ‘civilised’ world against the so-called ‘chaotic, dangerous’ Otherworldly faerie woman/goddess. Manawydan, as a sea god, very much represents the forces of the Otherworld, and thus Rhiannon taking him as her husband may represent a sort of ‘homecoming’ for her, as the sea was often thought to be associated with the Otherworld, or the portal through which one enters it. Horses, too, in some of the Celtic and other Indo-European thought seem to have been associated with the sea. Manawydan’s Irish cognate Manannán rode a magical horse named Enbarr, whose name means ‘froth’, bringing the image of the horse-like appearance of the frothy white waves. Rhiannon’s white mare has also been interpreted as one of these oceanic horses, too.

Compare the above to the other Faerie Bride love triangles, in many of which the Faery Bride ends up choosing to be with the ‘Otherworldly’ man, and you could argue that these stories serve as a warning to the real life human men who choose to be with a ‘Faery’-esque, ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’-esque woman. If you don’t respect her Faery ways, if you try to shame her, tame her, and can’t accept her for who shame is, she may leave you for a man who can.

Well said, I love the interpretation that the Manic Pixie Dream Girl can be viewed as a modern version of the Faery Bride or Faery Lover. I totally agree that women who are tapped into this Faery energy need to be respected for their viewpoints, not looked at as just someone to liven up the dull life of the man they are with (then later be expected to fit a Normie mold of what he expects her to be now that he’s happy)! I think many of us that hold deep resonance with Faery energy and who are Priestesses to Faery Queen Goddesses have experienced things like that with former lovers. I am very lucky to have long put that behind me (I’ve been with my husband for 10 years), and to have a man who appreciates my offbeat nature. Thank you for sharing this!

LikeLike

100%! It’s been quite the journey for me with that too, and I’ve known a lot of women who’ve had similar experiences.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly!

LikeLike